Adventures with Beethoven

Scene Two

Theory and Harmony 101

Music theory is the system that is used to explain how music is put together. Starting with the basic elements such as notes, rhythm, and pitch, and moving to more complex features including scales and chords, theory explains the notation used to write music and how a collection of notes, scales, and chords can be put together to form a unified piece of music.

Western music has long used the scale as the basis of music. A scale is a collection of notes that moves in an ascending (going up) or descending (going down) pattern, usually starting and ending on the same named note, C for example. Scales can vary based on how many notes they have and what pattern the notes follow. The most common scale in Western music uses eight notes, named A-B-C-D-E-F-G, spans an interval called an octave, and can begin on any of the notes. While the scale is the most common building block in modern music, older styles of music used a different version of a scale called a mode.

Modes

In the Medieval and Renaissance periods music was built around the modes. Each mode was a set scale pattern that also suggested a set of melodic characteristics. The name mode derived from the Latin word modus, meaning “measure, standard, manner, or way.” The idea of the modes was inspired by the Ancient Greek writings about music. Although there is a lot of existing writing about music, depictions of music, and fragments of notation, we can only guess what the music would have actually sounded like, since we don’t understand the notes.

The writings of the Ancient Greeks and Romans affected many parts of Western culture during the Medieval and Renaissance and music was no exception. Ideas about music were based on the thoughts of writers such as Plato and Aristotle. In the Ancient Greek system there were many mentions of modes which later musicians then adapted for their use.

Modes, sometimes also called tonaries, were first used to group religious chants around the beginning of the 9th century, C.E. The church modes were named after their ancient counterparts, although they are not the same scales. There were eight modes that were often divided into four pairs, with each pair sharing a main note which served either as the starting note (examples 1, 3, 5, and 7 below) or as the middle note (examples 2, 4, 6, and 8). The modes were called either by their names or by a number, usually Dorian was mode 1 and began on the note D, as seen in the example below. The modes that started with the main note were called authentic and the modes that had the main note in the middle were called plagal. If you can imagine playing these on a piano, usually the modes only used the white keys with no black keys to change the pitches. Occasionally a B Flat would have been used, but not often.

Each mode had two notes that were most important, the final and the reciting tone. The final was the main note of the mode that either started the scale (in the case of the authentic) or was in the middle (plagal). The reciting tone was the note five spaces above the beginning note in authentic modes and three above in the plagal modes.

By about 1550 modes had been accepted as the standard form and one of the first theory books was published by Henricus Glareanus, Dodecachordon. In this book Glareanus added four new modes which he numbered 9 through 12 and named them Aeolian, Hypoaeolian, Ionian, and Hypoionian. Later theorists built upon and expanded Glareanus’s ideas, notably Gioseffo Zarlino who revised Glareanus’ numbering and naming systems, instead starting Dorian on the note C. These two different systems became popular in different countries with Zarlino’s system being widely used in France, while Glareanus’ was popular in Italy.

The Eight Musical Modes, Wikipedia

Modes were used throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, most notably in chant for the Catholic Church. Although modes look like modern scales, they functioned differently; each mode had specific melodic ideas that were associated with it, expected locations for cadences (the chords that signify the end of a section), and a certain character or mood. Various medieval theorists wrote about which emotion each mode suggested. While there are some differences, some modes had a commonly accepted emotion such as happy for Lydian and pious for Hypolydian.

Neumes

As the modes continued to develop, so did music notation. For a long time, music had been taught as an oral tradition with melodies being shared from person to person and taught by rote. By the 9th century a form of notation was being developed within monastic communities throughout Europe. The notation gave the groups the ability to sing longer pieces, without having to rely solely on their memory. The system used symbols called neumes to indicate pitch by placing each one in relation to each other going up for higher pitches and down for lower ones.

Neumes for a chant, written without clef, Wikipedia

The Staff

In order to make it easier to tell where each pitch was, the staff was developed in the late 9th century. The Italian theorist Guido d’Arezzo is usually credited with its development. Initially only one line was added, usually a red line to indicate the position of the note C. Later a second line was added, often blue to indicate F. The next line to be added usually indicated the note G. Eventually the staff became four lines and three spaces with a clef at the beginning to indicate where C or F were on that particular staff. Eventually the staff developed to five lines and four spaces with a clef at the beginning. Modern clefs today still help indicate which lines on the staff are C, F, and G. The modern treble clef is sometimes called the G clef because it curls around the line for G, the bass clef is called the F clef, and the tenor and alto clefs indicate the location of C.

Example of later chant featuring more developed neumes and lines for reference, Wikipedia

(“Music Notation from an early 14th century English Missal”)

Early F Clef

Early C Clef

Modern Clefs, Wikipedia

Guido d’Arezzo not only came up with an early version of the staff, but also with a set of syllables that enabled him to teach chants to his singers more quickly. The first stanza of the hymn Ut queant laxis moved up the notes of the scale, with each half-line starting on the next note. Guido took the syllable from the beginning of each of these lines and assigned them to the notes of the scale, creating a helpful tool to remember the notes when learning a new song. The syllables in Guido’s system were “ut-re-me-fa-sol-la.” Shortly after the last note was added to this system with the syllable “si”, creating the whole scale. Some teachers changed the first note to “do” (doe) and the last note to “ti” that are now the more common forms and are utilized in modern solfège (soul-fejh). Like Guido’s version centuries ago, solfège allows musicians to quickly recognize notes and sing unknown tunes by utilizing the “do-re-mi” syllables. In many countries solfège is based on the note C always being the syllable “do,” in a version called “fixed-do.” Other systems use a “movable do” where the first note of the scale for the key on which the piece is based is called “do”. (If you have ever seen the movie The Sound of Music this is how Maria teaches the children to sing.)

Plaque outside the home of Guido showing the scale with syllables he developed, Wikipedia

It took longer for a system of rhythm to be added. One theorist, Franco of Cologne, suggested that the shape of each neume could indicate duration, however it took until the 14th century for this to become commonplace. This idea expanded and developed using different shapes to indicate whether notes were longer or shorter by half. A version of this system is what is used today where note lengths are based on a system of shapes and symbols, and increasing and decreasing divisions of duration. Bar lines to indicate the end of a measure (a segment of a larger musical piece that is defined by a given number of beats) were added later to make the compositions easier to read. As notation continued to develop it allowed for longer and more complicated pieces to be written and performed. Throughout the Medieval and Renaissance periods, sections of the Catholic Mass were set to music and became one of the most important types of musical compositions of the day.

Scales

Modes were used for centuries, especially in chant for the Catholic church. As music theory progressed, scales became the standard rather than modes. The most common scales became the major scale and the minor scale.

Each scale, major or minor, is based on a specific pattern of whole steps and half steps. If you imagine a piano keyboard, a half step is going from one note to the very next note on the piano without skipping one in between. A whole step has a note in between the two. In general major keys sound happier and more cheerful, while minor keys sound darker and sadder.

Piano keyboard, www.allaboutmusictheory.com

A major scale always follows the pattern of whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step. You can start on any note and as long as you follow the pattern, you will get a major scale.

Three Major Scales with whole step/half step pattern, www.earmaster.com

Minor scales are a bit more complicated than their major counterparts. For each note there are actually three different versions of the minor scale: natural, harmonic, and melodic. The reason there are different minor scales has to do with the functions of each note in the scale.

Each note in a scale has a name and a job-these names are sometimes called a degree. The first and last note of the scale is called the tonic, while the fifth note is the dominant and the seventh note is the leading tone. In a major scale, there is only a half step between the leading tone (note 7) and the repeat of the tonic (note 8). A half step sounds incomplete to our ears and wants to resolve by moving back to the tonic.

Major scale with movable do solfège syllables and degree names, provided by Michael Wheatley, Skagit Symphony

In the natural minor scale, the simplest version of a minor scale, the pattern is a whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step. This pattern leaves us without a leading tone at the end which makes the scale sound incomplete. To solve this, the seventh note of the scale is raised a half step to make a more traditional leading tone. This creates the harmonic minor scale which has the pattern whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, step and a half (also called an augmented second), half step. While this version of the scale sounds more correct to our ear, it still has some problems. The skip of a step and a half is somewhat difficult to use, especially when singing and can create a choppy melody.

Some composers prefer the third option, the melodic minor scale. In this scale notes six and seven are each raised a half step going up and they are both lowered coming down. By raising the seventh note, we get the leading tone that our ears expect, but without the awkward jump. The melodic scale ends up sounding a little like a hybrid of major and minor; it sounds mostly major going up, but all minor coming down. Its pattern is whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step going up, while coming down it is whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step. All three minor scales are used regularly depending on how the composer wants their piece to sound.

Comparing Types of Minor Scales, www.earmaster.com

An interval is the name for the space between notes. To find the interval simply count the names of the notes up the scale and that will give you the number, for example from C to G is five notes in the scale (C-D-E-F-G), making the interval a 5th. Intervals range from a 2nd (a whole or half step as in the discussion on scales above) to an Octave (8 notes from a C to a C for example) and can go beyond to 10th, 13th, or 15th. Each interval is also designated with a description of its quality, major, minor, perfect, augmented, or diminished. Being able to recognize intervals in a piece of music helps the musician as they play to know which notes they are seeing more quickly. When two or more intervals are played together at the same time, we get a chord.

Interval through unison octave, www.sfu.ca

Chords

A chord is a group of three or more notes played simultaneously. Each note of the scale can have a chord built on it. The chord can be identified by its bottom note (called the root) and is named based on its place in the scale such as tonic for the first note and dominant for the fifth. Chords are also given a Roman numeral designation. The chord built on the first note in the scale is chord I, while the chord built on the fifth note is V. Chords form the underlying harmonic structure for a piece of music and can be used played in blocks together or melodically. As a piece progresses, the composer uses a series of chords to move through a harmonic sequence. Much of music theory is based on understanding how chords work together, their relationship to each other, and finding the ways composers use chords in new and interesting ways.

Chords built on each note of the scale, www.earmaster.com

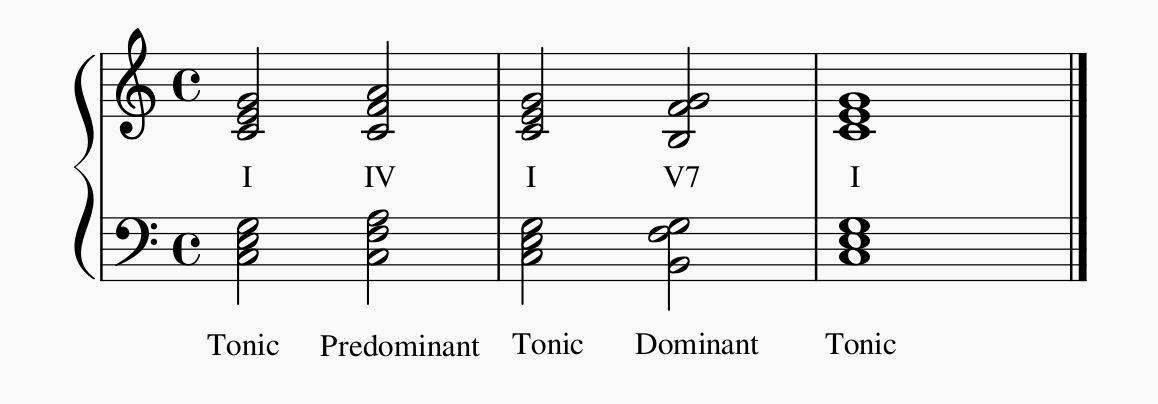

When chords work together to move through a sequence of harmonies over the course of a piece it is called a chord progression. There are certain chord progressions that are typical in Western music, whether it is a symphony, a blues piece, or a pop song. The most common chord progression is simply a move from I-V-I or tonic-dominant-tonic. Sometimes the composer will add a IV chord in between, creating a slightly more complex progression, I-IV-V-I or tonic-predominant (subdominant)-dominant-tonic.

I-IV-I-V7-I Chord Progression, provided by Michael Wheatley, Skagit Symphony

While this is the standard progression in major keys, minor keys are sometimes different. While a minor key can use the I-V-I progression, sometimes the progression will be I-III-I. Each major scale is related to a minor one that has the same notes, designated by a key signature that tells the musician if any notes have to be altered by a sharp, which raises the note a half step, or a flat, which lowers the note a half step. The key signature is notated at the beginning of each line of music. To find the relative minor key, go down three notes from the first note in the major scale. That new note, three steps below, will be the first note of the relative minor scale. For example from C go down three notes, C-B-A and A minor is the related key to C Major. In a minor key, sometimes the composer will go to the relative major key as they develop their composition.

In the Classical period composers used a new structure to organize their pieces called sonata form. In this form, as the piece develops, it uses a chord progression formula as the underlying harmonic structure. Sometimes chord progression can get very complicated as composers try to make their works sound new and different. Surprisingly, even in some of the most complex works, the main framework of many pieces are still the simple I-V-I progression.